In previous post I concentrated mostly on technical aspect of where Super Mario Run falls behind. I listed technical solutions or different game design which would greatly improve initial gameplay.

Here I want to concentrate on financial aspect of the game and the causes of poor App Store ratings. And no - saying that people are being jerks that don't want to pay for things is too simplistic and doesn't get us anywhere.

There are actually two issues with Nintendo's newest game. The first one is related to state of current App Store environment, the second is design choices that Super Mario Run creators made that changes the perception of it among other titles. Let me start with the latter.

The Coins

When you think of Free to Play (or F2P for short) games there are two rules that apply to most of them:

- They need to be actually free to play

- To generate revenue you charge for customization and for making the game easier to play

This means that you should be able to play the game without spending a dime on it. It might not be the best way to experience the game, but it should be possible in the long run. It usually leads to content of the game being available to everyone for free. You don’t split the community - paying and free users both experience essentially the same game. If you pay, you might “just” get more lives, more skins, get slightly better stats or you don’t have to wait as long as free users for in-game items.

It's important to keep the community as one group because very few users actually spend any money on F2P games. Depending on where you check, only 0.5% to around 6% of players pay anything. Imagine if those players had different content - let’s say - 3 additional maps. This would mean, that for every 200 people online, you might get only one person who could also play a paid map. Multiply it by the probability of you both choosing the same map and you get poor experience as a result. That's why, in most cases, content comes free.

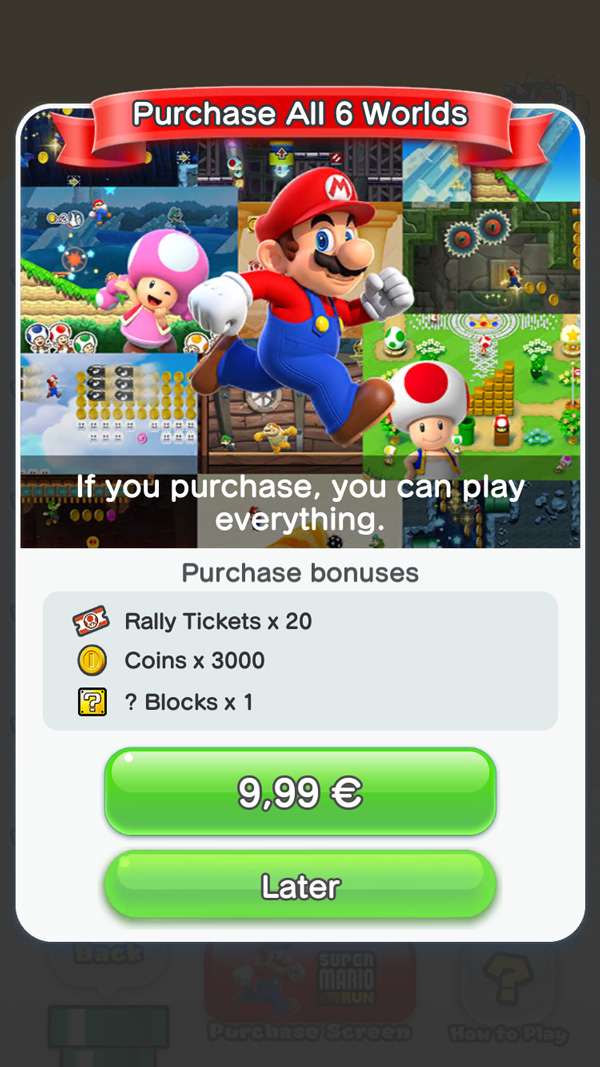

Why do I even mention Free to Play games? Super Mario Run isn't a F2P title, right? Well - we don't know for sure but there are a lot of things that player faces from the very beginning that could suggest different. Of course it's largely a matter of perception, but bear with me.

First of all, Super Mario Run is available for free. It's sort of a dumb argument, but without it we can't really talk about free to play game. To make money, it uses In-App Purchases, which can be anything. It can be just new level, which Nintendo is selling right now, but it can be anything within the game. There's nothing stopping Nintendo from changing that. Especially that it allows them to make money from both - new and existing users.

Another design that has emerged in the F2P game design are in-game currencies. The game has to have at least one in-game currency, but usually ends up with couple of them. Some (let’s call them coins) are usually easily available. You get them for interacting with the game, that's your reward for playing the game - it keeps you motivated to come back, earn more and spend it. Other (we'll call them diamonds) are more premium. Sometimes you can still earn them in the game, but are much harder to get and there are very few of them. Both of them can be bought by real money directly or by just earning more of them in game, if you're a paying customer.

Coins, caps, simoleons - they are all the same

Super Mario Run is not different in that regard. There are coins and there are tickets. You get coins by interacting with the game, you can play the same level over and over again and you'll always get 100+ more coins. Tickets are more premium currency. If you want to get them, there's basically only one "sure" way1 of getting those for free - once every 8 hours you can play a minigame and have 50% chance of getting one(!) ticket.

With those game coins you can buy some in-game customisations - new buildings and elements for your village which are mostly decorative. For other items you have to first earn Toads (which can also be treated as a currency). To get those you have to spend tickets - the premium currency - and play the Rally part of the game.

Is this really any different than Caps and Nuka-Cola from Fallout Shelter or Views and Subscribers from PewDiePie's Tuber Simulator? For now, in Mario, you can't buy those currencies with real money directly, but that's just a detail and no-one says that you won't be able to. It's actually quite likely to see an option in the future to buy something that will allow you to buy this building or character, without playing the game for 30 hours.

The point here is, even if Nintendo didn't plan it to be a standard Free to Play title (which I doubt), the game feels like one. It has all the mechanics of F2P title and you encounter them from the very first few minutes of experiencing the game.

But in contrast to normal Free to Play games, it also tries to charge you for content. This can lead to kind of cognitive dissonance, which can lead to radical drop in experience once the game asks you to pay for more levels.

Free to play? Demo?

The Store

The second issue is not a Mario Run specific one. It's a more general problem of the App Store and it all comes down to behavioural economics. Mario like many other apps just falls victim to it.

If I would ask a group of people how much should I charge for an iOS app, I will hear different answers. I'm sure there would be a free answer, I'm sure that $0.99 would be in there. And even if someone would give more vague answer, like "it depends on the app", I'm sure that for most, they would still think of something under 5 or 10 bucks, much closer 99 cents or magical free option.

The reason for this is the way our minds work and the way App Store worked at the very beginning. It's difficult to assess the value of something, especially if it's something somewhat new. To work around it our brain uses comparisons. We search for things that are in some way similar and have a specific, average price. Once we have it, we try to use some heuristics to guess the price, compared to what we know. In the early days of the App Store, that was kind of an advantage, since for many the closest thing that they could think of was a Mac application. And those did cost easily anywhere between $25 to $50 or more. Even if you would apply heuristic of - "well, the screen is smaller, so it had to take less time to do" or "I can't do all the things on my phone, that I could do on my powerful computer" you still had an advantage and could price your apps between 5 and 10 dollars without a problem.

But prices dropped rapidly. The App Store gold rush caused a lot of apps to be priced at the lowest tier of $0.99, hoping to make up the earnings in volume. Especially after reading about over-the-night success stories, which made millions by making a simple, cheap app. For most the dream never came. They went bankrupt, had to find some other way to make money, but the market has settled and 99 cents for paid app had become a de facto standard for most. Something that in most cases doesn't allow a sustainable income, but it's very hard to get rid of from the mind of the customer.

In that regard I actually root for Nintendo for setting the price higher than lower. The current business model isn't sustainable in the long run or causes the emerge of other, more shady in my opinion, models - like Free to Play games or aggregation and trading of personal data. The more developers and publishers will try to bring up-front prices higher, to levels which will allow to create new software and support existing one, the more chance we have to reverse the trend. But it's difficult, especially on a market where an average app did cost only $0.19 just 3 years ago. In other areas, like in food industry, they figured it out sooner. Instead of dropping prices, they use other tricks to cut down costs. In times of need, they lower the volume of their product, while sometimes keeping the package same, they change the recipes to use less or cheaper ingredients. But in development, where the biggest cost is experience and people, it's more tricky. And while everyone has to eat something, not everyone has to play your game. Unfortunately we didn't learn that soon enough how much of an impact and for how long does the price dumping have.

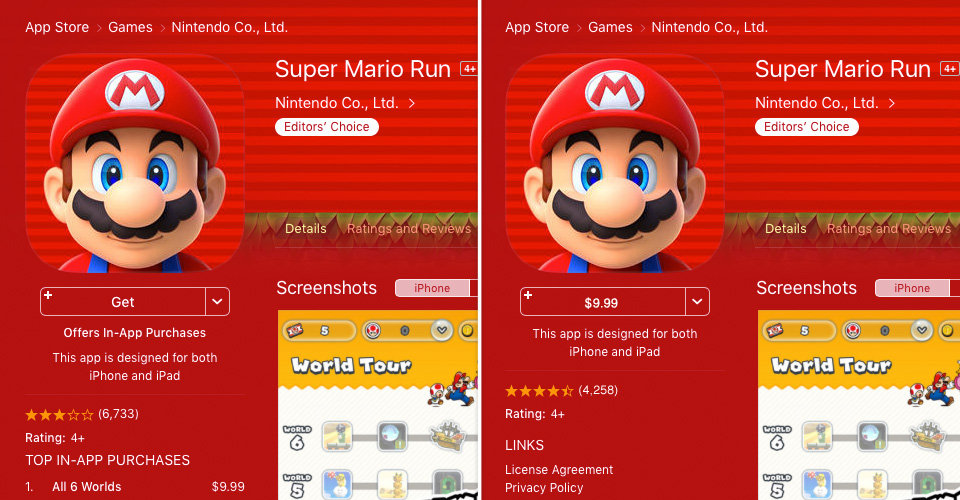

Which would you buy? Which would you rate higher?

There's also a special case of low price - free. Free has magical properties. It turns off our brains, turns off any cost-benefit analysis and leads us to make bad decisions. Dan Ariely, professor of behavioural economics did and experiment that illustrates this perfectly. In the experiment he offered two kinds of chocolates - a premium one priced at 15 cents and a cheap one for 1 cent. The cost-benefit analysis kicked in and 73 percent of people saw the better deal and chose premium chocolate. But when the price was reduced by 1 cent, making the cheap chocolate free, people started to act irrationally - choosing the cheap one 69 percent of the time, even though nothing really changed - the price difference stayed the same, making the premium chocolate still the better deal.

In this case App Store and chocolates are very similar - if we have a choice between free app and one that we have to pay for, we stop thinking rational and choose the free one. Even if the paid one is better designed, better written and is in our best interests to have a team that's able to support the app in the long run. It's just how our brains are wired and it requires significant amount of energy to work against it.

The Conclusion

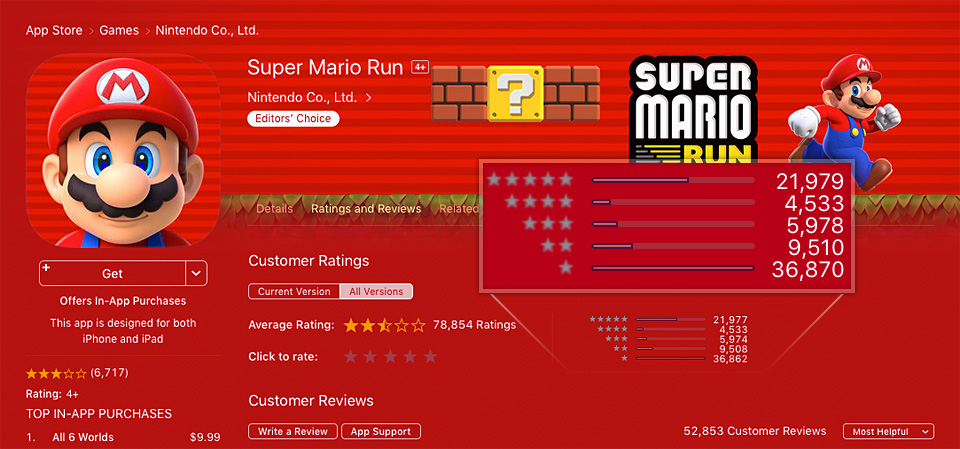

So as you can see, the problem is more difficult than just people being cheap. We have a large group of clients, not thinking rationally and in their best interests, because the way we perceive and calculate value of things. On one side we don't generally compare our digital purchases with other things. We don't think that the app costs the same amount as two burgers and will be useful for longer. We compare it with other apps, which in most cases are still underpriced, because other apps are priced that way. It doesn't also help that the app is available for free and has a lot of mechanics and design choices known from free to play games, which changes our way of perceiving it.

You add all those things together and you get a good game with a rating between 3 and 4 stars. It's really scary when you think about the fact that it's a game from major, well known and received company, from one of the biggest franchises in games history. And it was and is actively promoted by Apple and Nintendo for months.

Love it or hate it, there's very little in between

Post Scriptum

The scary part, lurking somewhere in the background, is - if companies like Apple and Nintendo can’t sway the public perception of price for apps, how a smaller company or even an indie developer can? Especially when there’s very little place for brand on the App Store, no room for conversation with your clients, almost no room for experimentation that could lead to better solutions and fair but sustainable business models.

Only Apple can change that. Because even if we design our apps just right, there’s still a problem that general public thinks that apps should cost very little, they should be supported for a long time and updates for them should be free. Even if Nintendo made enough thanks to all the promotion and despite the poor ratings, we have a big problem, one that can’t be solved alone, can’t be solved overnight with one decision.

We have a problem of perception, of how people feel and it is in best interest of every party involved to solve that problem. Including Apple, which used to care about how their clients feel, not just to get good consumer ratings but also as a way of thinking about their products and business.

1. To be exact - you can exchange Nintendo Points for more tickets and there’s also a chance of gaining one after getting all purple coins or by buying right buildings in your village, but those aren't really repetitive in-game tasks or require purchase anyway.